|

The Monastic Life

|

|||||

Stanley Roseman

The MONASTIC LIFE

The MONASTIC LIFE

''No one, I believe, in 1,500 years of Christian monachism has catalogued, defined

and described so clearly or so beautifully the business of the monastic life.

No writer, no sculptor, no painter, no architect has refined a distillation so pure,

so accurate, so breathtakingly clear as Roseman has done.''

and described so clearly or so beautifully the business of the monastic life.

No writer, no sculptor, no painter, no architect has refined a distillation so pure,

so accurate, so breathtakingly clear as Roseman has done.''

- The Times, London

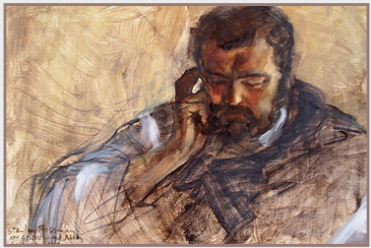

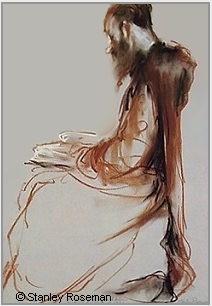

Dom Henry,

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Stanley Roseman embarked in 1978 on what the Los Angeles Times calls ''a sweeping artistic project.'' The artist was invited to live in Benedictine, Cistercian, Trappist, and Carthusian monasteries and to share in the day-to-day life in the cloister. Behind the monastery walls, Roseman painted portraits and made drawings of monks and nuns of the four monastic orders of the Western Church and created a monumental and critically acclaimed oeuvre on the monastic life - a life centered on contemplation and prayer.

"Through the centuries the monastic orders contributed greatly to the advancement of Western civilization. Nevertheless, in Western Art monastic life accounts for a small percentage of the extensive imagery on religious subject matter. From the thirteenth century there grew a popular demand for pictures of saints of the newly founded mendicant orders, which include the Order of Friars Minor, or Franciscans; Order of Friars Preachers, or Dominicans; Order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, or Carmelites; and Austin Friars. Franciscan and Dominican friars were especially common to the cityscape and actively sought contact with society in contrast to those who sought the contemplative life behind the monastery walls.''

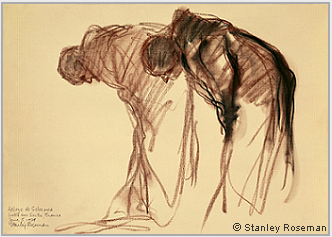

3. Two Monks Bowing in Prayer, 1979

Abbaye de Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Abbaye de Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Monastic Journey - Beginnings

5. Dom Henry,

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

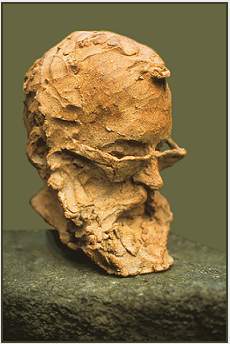

8. Father Ian,

Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation, 1978

Mount St. Bernard Abbey, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation, 1978

Mount St. Bernard Abbey, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

"Father Ian is for me an absolutely captivating work of art."

- Pierre Barousse, Curator

Musée Ingres, Montauban

Musée Ingres, Montauban

The Artist and the Trappists

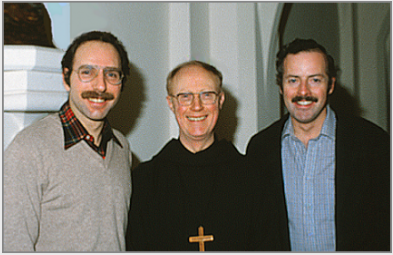

Abbot Gilbert, who was to be elected ten years later Abbot President of the Subiaco Congregation, told his two American guests that Roseman's work was "providential" as the monastic world was preparing to celebrate in 1980 the 1,500th anniversary of the birth of St. Benedict, Father of Western Monasticism and Patron Saint of Europe.

- François Bergot, Director

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Chief Curator of the Museums of France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Chief Curator of the Museums of France

The revival of monasticism in England in the nineteenth century brought the founding in 1835 of Mount St. Bernard Abbey, a member of the branch of Cistercian monasticism called the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, also known as the Trappist Order.

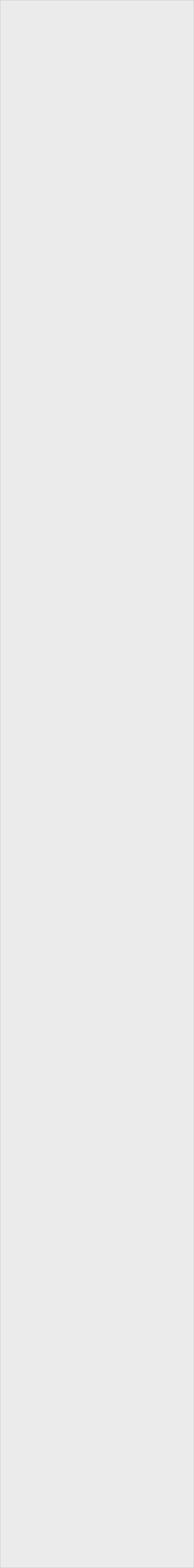

6. Mount St. Bernard Abbey, Leicestershire.

View from the monastery enclosure, looking towards

the scriptorium and dormitory (above),

the library (far right), and the church tower beyond.

View from the monastery enclosure, looking towards

the scriptorium and dormitory (above),

the library (far right), and the church tower beyond.

Mount St. Bernard Abbey, secluded in a part of Charnwood Forest, in Leicestershire, is a large monastic complex with an abbey church, conventual buildings, workshops, greenhouses, orchards, vegetable gardens, and farm buildings to accommodate a dairy herd which provided the monastery's main source of income.

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

The carpenter, a dark-haired, bearded monk named Ian, kindly provided Roseman with wood, tools, and a space in the carpentry shop to build the stretchers for his canvases. The artist's work includes beautiful portraits of Brother Raphael, a warm-hearted Irishman, (Private collection); the genial 83 year-old Scotsman Father Benedict wearing his gardener's hat as he sat for the artist on the balcony of the monks' dormitory, (Private Collection); as well as the carpenter Father Ian, whose portrait is in the Musée Ingres, Montauban, (fig. 8, below).

Abbot Cyril, Prior Luke, Guestmaster Father Mark, and the Community warmly welcomed Roseman and Davis to Mount St. Bernard Abbey. The Trappist monks invited the artist to draw them in church and brought him inside the enclosure to further pursue his work on the monastic life.

The Prior Father Luke writes to Davis: ''Your letter of the 6th of April has just come in and has been handed to me as the Abbot is at present away on a course in London. I have talked over the question of your visit with Mr. Roseman with several of the Community, and people seem happy about the idea.'' After thoughtfully offering suggestions for travel directions to the monastery, the Prior warmly closes: "Looking forward to seeing you and with all good wishes and prayers for the success of your venture.''

Stanley Roseman, who is of the Jewish faith, made the journey with his colleague Ronald Davis, of the Roman Catholic faith. Davis wrote the letters to monasteries to introduce his colleague's work, relate the artist's interest in monastic life as a subject for his paintings and drawings, and make a request for a sojourn. As neither Roseman nor Davis had sojourned in a monastery, they thought to experience monastic life for the first time in their native language. Davis initially wrote from New York to monasteries in England and Ireland. Participating in the research and in planning the itinerary, Davis organized the project, as he had done for their journey in 1976 to Lappland, where Roseman painted portraits of the nomadic Saami people. The Times, London, states: "The Saami paintings are magnificent.'' (See "Biography.'')

The first letter Davis and Roseman received from a monastery was a cordial invitation from Abbot Gilbert Jones of St. Augustine's Abbey, a Benedictine monastery on the coast of Kent and named for the sixth-century monk who was the first Archbishop of Canterbury. St. Augustine's Abbey dates from the mid-nineteenth century, with a direct lineage to the Abbey of Subiaco, founded in the sixth century by Benedict of Nursia (c.480-547), whose rule, known as the Rule of St. Benedict, is the basis for monastic observance in the Western Church.

Abbot Gilbert writes enthusiastically that Roseman's prospective work on the monastic life "sounds most exciting and of course you may start off here. . . .'' The Abbot thoughtfully mentions that he could suggest other monasteries and encourages them to go to Subiaco, where "St. Benedict began his search for God - a glorious place and full of a very special character.'' Abbot Gilbert was reassuring that between St. Augustine's and Subiaco "there are many possibilities for a fascinating pilgrimage,'' and reaffirming his invitation concludes: "Let me know when to expect you.''

On the afternoon of their arrival at St. Augustine's Abbey, in April 1978, Roseman and Davis were warmly greeted by Abbot Gilbert, who came to meet his two guests in the entrance hall of the monastery.

Roseman recounts: "Abbot Gilbert was as cordial in person as he was in letter and heartily welcomed Ronald and me to St. Augustine's Abbey."

Next to the carpentry shop was the pottery where Roseman drew the bearded, bespectacled Father Bernard at his potter's wheel. Father Bernard had established a thriving workshop that produced excellent quality earthenware pottery which provided a substantial income for the monastery.

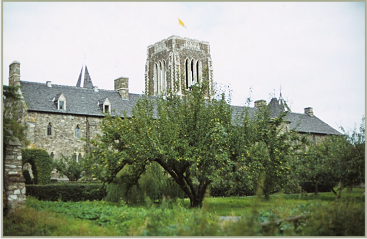

7. Father Bernard, the Potter, 1978

Mount St. Bernard Abbey, England

Terra cotta, height 50 cm

Collection of the artist

Mount St. Bernard Abbey, England

Terra cotta, height 50 cm

Collection of the artist

Reproduced here is Roseman's impressive terra cotta bust Father Bernard, the Potter, (fig. 7). The artist writes in his journal:

"The drying and firing of the terra cotta needed great care, especially as I had modeled Bernard's eyeglasses as sculpted forms unto themselves. Bernard decided to slow the drying process of the sculpture over three weeks, and then instead of making the customary one firing, to make two, at increased temperatures to avoid breakage. In the interim, Ronald and I left for monasteries in Ireland with the intention to return to England at the end of August. When the terra cotta sculpture had dried, Bernard made a bisque firing at a low temperature followed by a stoneware firing at a higher temperature of 1,300 degrees centigrade in an open flame kiln.

"In Ireland, Ronald and I received a welcome letter from Bernard reporting that the sculpture had 'survived two firings!!!' Bernard happily went on to say the sculpture 'looks fine - colour toasty, uneven in the sense it is not a flat colour throughout. Size I reckon is exactly life-size. All joy and love, Bernard.' "

Roseman is asked to give a Talk on his Art to the Monks

Abbot Cyril asked Roseman to give a talk on his art as the monks expressed much interest in seeing him at work in the monastery. The Abbot reserved an evening between supper and Compline, the last office of the day. The guestmaster Father Mark with Father Bernard set up a screen for viewing slides in the scriptorium. Roseman spoke about his work on the performing arts, which included opera, theatre, dance and the circus in the United States; paintings of the nomadic Saami people of Lappland; as well as landscapes, still lifes, and portraits.

"I was honored to be speaking to a gathering of Trappist monks in their scriptorium," Roseman recounts, "and sincerely grateful for their interest and enthusiasm for my work. The monks also expressed great pleasure in the work I was creating at Mount St. Bernard, which could not have been without their hospitality and encouragement."

Roseman's talk to the monks of Mount St. Bernard Abbey was the first of a number of talks he was asked to give to communities of monks and of nuns as the artist continued his work in monasteries throughout Europe.

"an absolutely captivating work of art"

"By the late sixth century, monasteries were flourishing in Gaul, on the Italian peninsula, and in the British Isles. Irish monks brought the ascetic practices and scholarly pursuits of Celtic monasticism to the Continent as other contemplatives venturing north from Italy crossed the Channel to England. . . .

Roseman's ecumenical work, brought to realization in the enlightenment of Vatican II, depicts monks and nuns of the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran faiths. Roseman created his work in over sixty monasteries throughout England, Ireland, and Continental Europe. The artist writes:

Two Monks Bowing in Prayer, 1979, (fig. 3), is conserved in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Roseman drew this spiritual work of art at the Divine Office at the Abbey of Solesmes.

In choir, Roseman drew the community praying and chanting the Psalms at Matins and Lauds in the early morning, at the canonical hours throughout the day, and at Vigils in the night. Psalmody, which traces its origins to the singing of the Psalms in ancient Jewish liturgical worship in the Temple and the Synagogue, is the foundation of the Divine Office, the daily round of communal prayer that is central to the monastic life.[9]

The warm reception and great encouragement Roseman and Davis received at St. Augustine's Abbey that April 1978 was an auspicious beginning to the artist's work on the monastic life.

An Unprecedented Work on the Monastic Life

''When I began researching and planning my work on the monastic life, my thoughts were towards Europe for monastic life is interwoven with the history and culture of Europe. . . . [1]

Sharing in the day-to-day Life in the Cloister

Sharing in the day-to-day life in the cloister, Roseman drew monks and nuns in prayer and meditation and at various kinds of work. The artist drew monastic communities taking meals in silence in the refectory. He drew individuals studying in the library, writing in the scriptorium, and at afternoon tea or coffee in the calefactory.

A major part of Roseman's work on the monastic life is expressed in the medium of drawing, considered the foundation of the visual arts. The celebrated, sixteenth-century Florentine architect, painter, and author Giorgio Vasari writes in the preface to his famous series of biographies Lives of the Artists that drawing (disegno) is ''the parent of our three arts, Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting, having its origin in the intellect.''[8]

The Monastic Life continues

with links at the bottom of this page

to the following pages:

with links at the bottom of this page

to the following pages:

2. The Emerald Isle

3. On the Continent

to Belgium, the Netherlands,

and Germany

to Belgium, the Netherlands,

and Germany

4. Across the Continent

to Austria, Hungary, and Poland

to Austria, Hungary, and Poland

5. South to Italy

and the Abbey of Subiaco

to conclude the artist's first year

of his work on the monastic life.

and the Abbey of Subiaco

to conclude the artist's first year

of his work on the monastic life.

"With the expansion of Benedictine monasticism throughout Europe in the Carolingian Age and Cistercian monasticism in the Twelfth Century Renaissance, the monastic orders - adhering to the precept ora et labora, prayer and work - continued to encourage spiritual ideals; introduced new styles of architecture with the Romanesque and early Gothic; and furthered the development of agriculture, as did the Cistercians, in particular, by expert management in land cultivation on a large scale at a time when the feudal system was declining in efficiency. . . .[2]

"Monasteries made important contributions in music, such as the invention of staff notation by the Benedictine monk and music theorist Guido of Arezzo (c.995-1050), whose innovative use of syllables to refer to notes is the basis of the standard musical scale - the so-called 'do, re, mi scale' of today. . . .[4]

"Numerous European towns and cities owe their origins to the founding of monasteries and the settlements that grew up around them.[3] Monasteries offered employment to the local population; operated pharmacies supplied with medicinal herbs grown in monastery gardens; maintained hospices, especially for the poor and infirm; and administered schools. . . .

4. Stanley Roseman, Abbot Gilbert Jones, and Ronald Davis,

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England, 1978.

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England, 1978.

"From the sixth to the twelfth century, monasteries produced most of the books in the West. Scribes copied and illuminated manuscripts, and monastic authors wrote on a variety of subjects, religious and secular. An early example is A History of the English Church and People by the Venerable Bede (c.673-735), the Benedictine monk esteemed as the Father of English History. . . .

"It is of special interest to me, having created work on the monastic life, that a monk compiled the earliest extant manual in Western art on the formulas and technical processes used by artists and craftsmen for the preparation of pigments and materials. De diversis artibus (The Various Arts), a treatise divided into three books on painting, glass-making, and metalwork, was authored by a twelfth-century Benedictine monk who was himself a practicing metalworker and wrote under the pseudonym Theophilus. . . .[5]

"Many monasteries throughout Europe in the Middle Ages were intellectual centers of renown. . . .[6] The tradition of learning in monasteries was continued in the Renaissance, such as at Camaldoli, in the Apennines, and at the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, in Florence, where the Benedictine monks took an active part in the flourishing of Renaissance humanism. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Paris, the Abbey of St. Germain-des-Près, headquarters of the Benedictine Congregation of St. Maur, held regular gatherings of scholars and intellectuals, maintained an impressive library, and produced a copious literary output which included Dom Bernard de Montfaucon's fifteen-volume Antiquité expliquée, a forerunner to the modern study of art history. . . .[7]

Roseman and Davis were given rooms in the monks' dormitory, took their meals with the monks in the refectory and afternoon tea in the common room; studied in the monastery library; and accompanied the monks to the daily round of prayer in church and chapel. With great encouragement from Abbot Gilbert and the Community, Roseman began his work on the monastic life.

Dom Henry was acquired in 1986 by the Chief Curator of the Museums of France, François Bergot, for the renowned collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, of which he was the Director. Davis, whose maternal ancestry is French, had introduced his colleague's work to the Rouen Museum.

The painting joined a previous acquisition by François Bergot for the Rouen Museum of "two very beautiful drawings by Stanley Roseman'' from the artist's work on the monastic life. In a cordial letter to Roseman to acknowledge the acquisition of the portrait Dom Henry, the Chief Curator of the Museums of France writes:

"As you undoubtedly already know, I have expressed

to Monsieur Davis my admiration for this work of art

of profound insight and spirituality."

to Monsieur Davis my admiration for this work of art

of profound insight and spirituality."

Moreover, the founding members of St. Augustine's Abbey were English monks from Subiaco - the birthplace in the sixth century of Benedictine monasticism. The Order of St. Benedict, also known as the Benedictine Order, gave rise to the Cistercian Order in the eremitical movement of the eleventh century, which in turn gave rise to the rigorous asceticism of Trappist monasticism that developed during the seventeenth century.

Father Ian, Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation, 1978, Mount St. Bernard Abbey, is conserved in the Musée Ingres, Montauban, (fig. 8). The Museum's outstanding collection originated with an important bequest by Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres (1780-1867) of his paintings and drawings to his hometown. The bequest includes works from Ingres' collection of the Italian schools of the 15th and 16th centuries and French schools of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. The Museum's collection has since been augmented by works of modern art.

"this work of art of profound insight and spirituality"

"Over several days, I sculpted a portrait of Bernard while he worked at his potter's wheel. I had asked him if he had clay with a grainy texture that would fire to a natural color, rather than the smooth, gray clay generally used for throwing pots. Bernard suggested a clay that seemed right for the portrait I intended to sculpt. I was happy with the feel of the clay in my hands, and sculpting the portrait of my friend went well. However, the density of the clay, even after the finished sculpture was hollowed out, presented a challenge for a successful firing.

The Curator of the Musée Ingres, Pierre Barousse, made the first acquisition of Stanley Roseman's work for the Museum in 1986 with the drawing entitled A Carthusian Monk at Vigils, 1982, Chartreuse de la Valsainte, Switzerland. (See page "Benedictines, Cistercians, Trappists, and Carthusians.") Father Ian, Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation entered the collection of the Museum in 1987.

Roseman painted the superb portrait of Ian in the carpentry shop after the monk had finished his day's work. The striking mise-en-page with descriptive charcoal lines setting the composition onto the canvas and calligraphic brushstrokes rendering form and space are complemented by chiaroscuro modeling of the monk's strong facial features with dark hair and beard. Head and shoulders are silhouetted against a summary background of warm earth tones. Highlights on the tunic and collar add brilliant accents to the portrait.

Roseman has expressed serenity on the face of the Trappist monk, his right hand resting on his cheek and temple as he meditates at the end of his workday in anticipation of the monastery bell summoning the community to Vespers.

Dom Henry, Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978, St. Augustine's Abbey, is presented at the top of the page and here, (fig. 5). The rapport between the artist and the monk is evident in Roseman's magnificent portrait of Dom Henry, who was in his early seventies when he kindly sat for the artist.

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Photo by Ronald Davis

© Photo

- J. Carter Brown, Director

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The French Benedictine Abbey is renowned for the study and restoration of Gregorian chant, a reverential musical expression associated with singing the Psalms. The chant developed mainly in the context of monastic life, with the golden age of composition of Gregorian chant dating from the fifth to the eighth centuries.[10]

The drawing of two monks bowing in prayer from Solesmes was featured in the review of Roseman's work in The Times. London, 1980, from which is the quote at the top of the page. The superlative review also presents a drawing of Brother Alberto, the cook, whom Roseman drew at the Cistercian Abbey of Poblet, in Spain, in summer of 1979; and a portrait of Don Egidio Gavazzi, Abbot Emeritus, from the Benedictine Abbey of Subiaco, in central Italy, where the artist concluded in December of 1978 the first year of his work on the monastic life.

". . . how very pleased we all are to acquire this fine example of your drawings."

"May I add my own warmest personal thanks for your interest in the Graphic Arts Department of the Gallery and say how very pleased we all are to acquire this fine example of your drawings."

In letter to Davis, who introduced his colleague's work to the Musée Ingres, the distinguished Curator writes:

A luminous pictorial space envelopes the figure of the monk clothed in his black Benedictine habit. In a masterly rendering of the face of Dom Henry looking directly out from the canvas, Roseman has created a portrait with a powerful presence of a man who has dedicated his life to meditation and prayer in the search for God.

''The project is a splendid artistic collection, an historic record of a way of life never seen before on such a scale," enthuses Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, in its Sunday magazine color feature story in 1980 regarding Stanley Roseman's work on the monastic life.

When Roseman began painting and drawing in monasteries in the late 1970's, monastic life was little known to the general public and an unfamiliar subject for a modern artist's work. Monastic life was rarely a topic for coverage in the popular press. Unlike today, monasteries then were closed to television cameras and documentary filmmakers, and the Internet, with its vast information resources, did not exist. Roseman's work on the monastic life brought a new awareness of the centuries-old and far-reaching contemplative tradition in Western culture.

The respected art journal ARA arte religioso actual, Madrid, published in the fall of 1979 a laudatory reportage entitled ''Stanley Roseman y la Vida Monastica'' and states:

''The pictures - splendid and telling all at once - form the stimulating vanguard

towards so original and deep a study of the monastic life.''

towards so original and deep a study of the monastic life.''

- ARA arte religioso actual, Madrid

A. Toubeau, S.J., of the editorial board of the Jesuit publication Nouvelle Revue Théologique writes:

"This very life-like portrait admirably conveys the intense spirituality of Dom Henry; one cannot help being struck by the depth and intensity of his regard. To render the expression with such truthfulness, it would be that the painter himself shares in some way the high virtues of his model. And this portrait will also help us share in the contemplative fervour and the experience of the divine intimacy which are the essentials of the monk's life.''

- A. Toubeau, S.J.

Nouvelle Revue Théologique

Nouvelle Revue Théologique

The Monastic Life

"It is a pity that I cannot express adequately my feelings in English to say how I have been moved by your text. Father Abbot gave me the text before Compline and so I read it during the night till I had finished, because I was caught directly.

"It is a marvellous text. It is not simply an introduction, but a text that is not only scientific, but above all personal and full of deep understanding of the monastic life."

- Brother Thijs

St. Adelbert Abbey

St. Adelbert Abbey

Brother Thijs, a Biblical scholar and the librarian at the Benedictine Abbey of St. Adelbert, kindly made the library available to Roseman and, as did other monks and nuns during his sojourns in monasteries, assisted the artist with his study and research on monasticism and encouraged him in writing a text to accompany his paintings and drawings on the monastic life.

Quoted to the left are excerpts from the artist's text. Having read a draft of the manuscript, Brother Thijs writes in his letter of June 1986 to Roseman:

The Director of the National Gallery of Art, J. Carter Brown, cordially writes to Roseman on May 7, 1981, to say that the Museum's Board of Trustees at their meeting that day "gratefully accepted" the artist's "generous offer" to make a gift of his drawing from the Abbey of Solesmes in loving memory of his father, Bernard Roseman. The eminent Director concludes his letter of appreciation to the artist:

2. Brother Thijs in the Library, 1982

St. Adelbert Abbey, the Netherlands

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Graphische Sammlung Albertina

Vienna

St. Adelbert Abbey, the Netherlands

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Graphische Sammlung Albertina

Vienna

10. Ibid., p. 101.

1. The quoted excerpts are from a text Roseman has written on monastic life and his work in monasteries to accompany his paintings and

drawings. The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green read a draft of Roseman's manuscript and writes in a cordial letter

to the artist: "You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

drawings. The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green read a draft of Roseman's manuscript and writes in a cordial letter

to the artist: "You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. Louis J. Lekai, The Cistercians (Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1977), see Chapter 20, pp. 282-333.

3. Pierre Riché, The Age of Charlemagne (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1978), pp. 32-39.

4. New Oxford History of Music, Vol II, "Early Medieval Music up to 1300,'' ed. by Dom Anselm Hughes

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954), pp. 290-292.

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954), pp. 290-292.

5. See Theophilus The Various Arts, translated from the Latin by Charles R. Dodwell (Oxford & New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons), 1961.

6. Charles Homer Haskins, The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1927), p. 32, 33.

7. David Knowles, Great Historical Enterprises (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd, 1962), pp. 35-62.

8. Giorgio Vasari , Vasari on Technique (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1960), p. 205.

9. New Oxford History of Music, pp. 1, 93, 94.