|

Benedictines, Cistercians,

Trappists, and Carthusians |

|||||

Stanley Roseman

The MONASTIC LIFE

The MONASTIC LIFE

Benedictines, Cistercians, Trappists, and Carthusians

The FOUR MONASTIC ORDERS of the WESTERN CHURCH

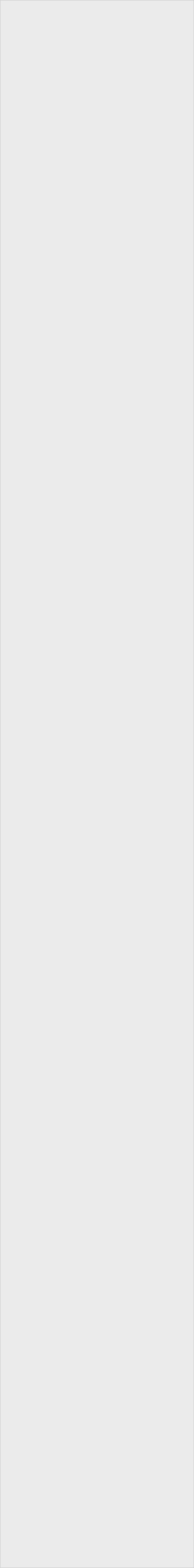

Padre Valeriano in Prayer

Abbey of San Pedro de Cardeña,

Spain, 1998

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Abbey of San Pedro de Cardeña,

Spain, 1998

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France

''Oh,'' replied he, ''at foot of the Casentino

crosses a stream named Archiano,

which rises in the Apennine above the Hermitage.''[2]

crosses a stream named Archiano,

which rises in the Apennine above the Hermitage.''[2]

- Dante, The Divine Comedy

2. The Holy Hermitage, or Sacro Eremo, of Camaldoli,

Tuscany, winter of 1979

Tuscany, winter of 1979

"Monasticism in the Western Church takes two forms: the cenobitic, or communal life, which is practiced by Benedictines, Cistercians of the Common Observance, and Cistercians of the Strict Observance, also known as Trappists; and the eremitic, or solitary life, practiced by Carthusians. At Camaldoli, both cenobitic and eremitic monasticism are combined in one monastic community.

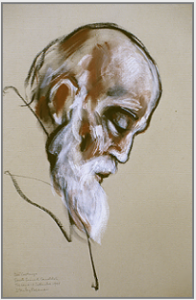

"The Prior General was younger-looking than his sixty-five years, even with his gray hair and white beard closely cropped on his cheeks and jaw but wispy and long on his chin. His eyes shone brightly, and with a fatherly smile and kindly manner, Padre Benedetto welcomed Ronald and me to Camaldoli.

3. Ronald Davis (left); Don Benedetto Calati,

Prior General of the Camaldolese Congregation (center); and Stanley Roseman (right),

Camaldoli, Tuscany, winter 1979.

Prior General of the Camaldolese Congregation (center); and Stanley Roseman (right),

Camaldoli, Tuscany, winter 1979.

"A gracious man, Padre Benedetto heartily assured us that we could stay at Camaldoli for as long as we needed for our work. He thoughtfully made arrangements for Ronald and me to move from the guesthouse into the cloister of the Monastery. We lived on the ground level which contained cells for the younger monks and allowed us direct access to the quadrangle of the beautiful, sixteenth-century cloister. The cloister garden, even in its winter slumber, was conducive for meditation. And so, with the warm welcome we received and the sparse but cosy quarters provided us, Ronald and I settled into life at Camaldoli."

At the Hermitage

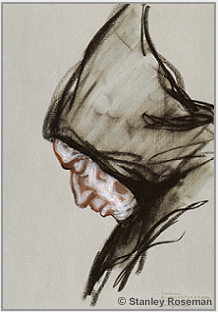

In a striking departure from Christian iconography that usually depicts hermits as elderly men, Roseman has depicted a young man in the beautiful red chalk drawing The Young Hermit Paolo in Choir, Hermitage of Camaldoli, 1979, in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique - Art Moderne, Brussels, (fig. 5). Writing about his work at Camaldoli, Roseman further recounts:

Returning to Camaldoli

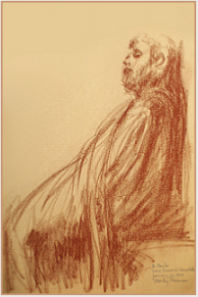

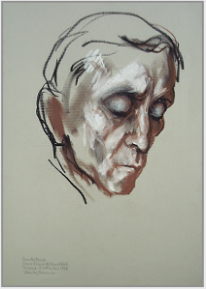

8. Don Antonio,

Portrait of a Hermit, 1998

Sacro Eremo di Camaldoli

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Collection of the artist

Portrait of a Hermit, 1998

Sacro Eremo di Camaldoli

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Collection of the artist

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

"From the dawn of the Renaissance, Camaldoli nurtured the development of humanism. Cosimo de' Medici (1389-1464), Pater Patriae, patriarch of the great House of Medici and humanist, was educated at the school of the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, in Florence. Cosimo's older contemporary and friend Ambrogio Traversari (1386-1439), also educated at Santa Maria degli Angeli, was a monk and outstanding classical scholar who was elected Prior General of the Camaldolese Congregation.

"When Ronald and I arrived at Camaldoli on that snowy January 2, 1979, we were aware of the great significance the invitation meant to my work on the monastic life.

"Padre Benedetto asked me if I would like to draw at the Sacro Eremo," recounts Roseman, "although I am sure he knew the answer to his question. I was deeply appreciative of the invitation to the Holy Hermitage, and the thought of such an experience filled me with great excitement.

- Dr. Henri Pauwels, Chief Curator

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique

- Phil Mertens, Chief Curator of Modern Art

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique

The Hermitage of Camaldoli Revisited

Taking up his paper and chalks in the late Tuscan summer of 1998, Roseman resumed drawing the monks at the Monastery and returned to draw at the Sacro Eremo. The artist recounts:

7. Stanley Roseman with Don Antonio,

hermit and astronomer,

showing the workings of his telescope

in the garden of his hermitage,

Sacro Eremo, Camaldoli, winter 1979.

hermit and astronomer,

showing the workings of his telescope

in the garden of his hermitage,

Sacro Eremo, Camaldoli, winter 1979.

Cenobitic and Eremitic Monasticism

The Four Monastic Orders of the Western Church - continued

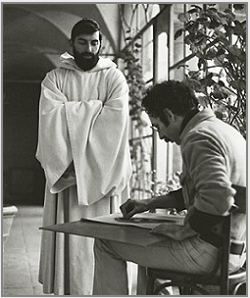

4. Stanley Roseman drawing Brother Emilio

in the Monastery Cloister, Camaldoli, 1979.

in the Monastery Cloister, Camaldoli, 1979.

"Camaldoli was founded in c.1023-24 by St. Romuald of Ravenna, who established a group of hermit dwellings and a chapel on a gift of land at 1,100 meters in the Tuscan-Romagna range of the Apennines.[3] At an existing refuge lower down the mountain, at about 800 meters, Romuald assigned several monks to provide food and lodging for travelers and pilgrims crossing the mountain pass. The refuge became a monastery maintaining a guesthouse. The monastery and hermitage formed a single monastic community. By the twelfth century, Camaldoli was the head of a cenobitical-eremitical congregation, with more than twenty monasteries and hermitages,[4] in the Order of St. Benedict, also known as the Benedictine Order.

Don Benedetto Calati and the monks were greatly encouraging to Roseman in his work on the monastic life. With paper and chalks, the artist accompanied the monks into church and chapel to draw them at the Divine Office, the daily round of prayer that is central to the monastic life.

The traditional Benedictine habit worn by monks consists of a black tunic, scapular, and hood. The cowl, a voluminous outer garment with a hood and long, wide sleeves, is worn in choir and also traditionally made of black material. There are several variations to the Benedictine habit. The Camaldolese monks wear a white tunic and scapular as well as a white cowl.

"Stanley Roseman lived in monasteries

of monks and nuns of the four contemplative orders throughout Europe

and created an extensive oeuvre of chalk drawings

profoundly expressive of the individual and the interior life''[1]

of monks and nuns of the four contemplative orders throughout Europe

and created an extensive oeuvre of chalk drawings

profoundly expressive of the individual and the interior life''[1]

"a sweeping artistic project''

Los Angeles Times praises Roseman's work on the monastic life as "a sweeping artistic project.'' This unprecedented and ecumenical work includes communities of monks and nuns of the Roman Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran faiths. Stanley Roseman is an artist of the Jewish faith.

The Monastery and Hermitage of Camaldoli

The invitation from the renowned Monastery and Hermitage of Camaldoli in the forested, upper Casentino region of the Apennines, in Tuscany, was of great significance to Roseman's work on the monastic life for Camaldoli holds a unique place in the history of Western Monasticism.

At the Monastery

"The Prior General Don Benedetto Calati was a renowned monastic scholar, author, and founding member of the Monastic Institute, established in 1952 and incorporated in the Theological Faculty of the Pontifical Athenaeum of St. Anselmo, in Rome.

Ronald Davis, who wrote letters to the monasteries to introduce his colleague's work and explain their request for a visit, participated in planning the itinerary and organizing the project. They began their second year of travels to the monasteries at Camaldoli, situated in the forested upper Casentino region of the Apennines.

From Roseman's first sojourn in a monastery, a Benedictine abbey on the coast of Kent, in April 1978, the breadth and geographical scope of his work over the following months and years brought the artist into more than sixty-five monasteries from England to Ireland and across the Continent to Eastern Europe; from Sweden, during the season of the midnight sun, to Spain at Christmas. "The pictures - splendid and telling all at once - form the stimulating vanguard towards so original and deep a study of the monastic life,'' states the respected art journal ARA arte religioso actual, Madrid, in its reportage ''Stanley Roseman y la Vida Monastica.''

Roseman's interest in the monastic life, which he notes is "interwoven with the history and culture of Europe;'' his studies on monasticism; and with the encouragement of monks and nuns, the artist wrote a text on monasticism and his work to accompany his paintings and drawings. The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green kindly read a draft of the manuscript and writes in a warm letter to the artist: "You portray the background and aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life. . . . Your descriptions of the monasteries you visited are very evocative, setting the scene for your portraits and giving such a very vivid impression of the life as it is followed in all its variety. I found it easy to imagine the monasteries that I had never visited, and certainly recognized those that I had, from your accounts of them.''

The following are excerpts from Roseman's text where he speaks about Camaldoli:

Roseman's work on the monastic life spans the years with cordial invitations from Benedictine, Cistercian, Trappist, and Carthusian monasteries. The monks' and nuns' high esteem for the artist's paintings and drawings; their admiration for his knowledge of monastic history; and their appreciation of his own contemplative nature earned Roseman enduring friendships and repeated invitations to take up again his work in their monasteries.

"Lorenzo de' Medici, called Il Magnifico, inherited the humanist ideals of his grandfather. In the second half of the fifteenth century, Lorenzo, his brother Giuliano, and other distinguished members of Florence's Platonic Academy, including the philosopher Marsilio Ficino; poet and man of letters Cristoforo Landini; and architect and art theorist Leon Battista Alberti gathered at Camaldoli for study and discourse in the newly built conference room, called the Hall of the Academies, in the guesthouse of the monastery.[5]

When the Monastery received in 1986 a Christmas gift from the artist of a reproduction of his drawing Two Monks Bowing, Abbey of Solesmes, collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C., Don Bernardino wrote Roseman a thoughtful letter saying that his drawing is "very beautiful and meaningful'' and that the publication of his work "will be appreciated by everybody, especially the monks." Don Bernardino closes, "I hope we will see you again; meanwhile I greet you and Ronald, with my best regards and wishes.''

"Don Benedetto Calati held the title Prior General as the superior of the Monastery and Hermitage of Camaldoli and head of the Camaldolese Congregation of the Order of St. Benedict.

In the summer of 1998, Roseman and Davis returned to the Monastery and Hermitage of Camaldoli. Don Benedetto, who was eighty-four and in frail health, had retired as Prior General, and his successor Don Emanuele Bargellini renewed the gracious hospitality from nineteen years before.

The Sub-prior Don Bernardino Cozzarini wrote the letter of invitation to Roseman and Davis. Don Bernardino had been in correspondence with the artist in years past and was also greatly encouraging of his work. During the mid-1980's when Roseman was much engaged in writing on the monastic life, Don Bernardino kindly sent him copies of the Camaldoli publication Vita Monastica, a scholarly journal whose contributors included Don Benedetto, Don Emanuele, and Don Bernardino, who in 2005 was elected Prior General.

Several of Roseman and Davis' neighbors in the cells in the lower cloister expressed their encouragement by kindly offering their time to the artist, as did Brother Emilio, who wore his white cowl and stood for the artist in the cloister, as seen in the photograph here, (fig. 4).

A major part of Roseman's oeuvre on the monastic life is expressed in the medium of drawing, considered the foundation of the visual arts. The celebrated sixteenth-century Florentine architect, painter, and author Giorgio Vasari states in the preface to his famous series of biographies Lives of the Artists that drawing (disegno) is ''the parent of our three arts, Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting, having its origin in the intellect.''[6]

Although drawings have traditionally served as studies or drafts in preparation for compositions to be realized in another medium, drawings can be works complete unto themselves. The artist's signature on a drawing, as well as a date or an inscription as to the identity of the sitter or place, confirms the artist's intention of having created an autonomous work. Roseman is a prolific and versatile draughtsman whose drawings, encompassing a range of subjects in a variety of drawing materials, are autonomous works of art.

Roseman and Davis were invited to take their meals with the monks in the refectory. "The dinners and suppers were simple but hearty," Roseman writes, "and the pasta, of different kinds and preparations, was always plentiful and delicious. As did some of monks at breakfast, Ronald and I also applied a little olive oil on our bread to enjoy with a flavorful cup of coffee."

© Photo by Ronald Davis

© Photo

"St Benedict in the Epilogue of his Rule (Chapter 73) counsels the monk to be guided by the Holy Scriptures, the Lives of the Fathers, the Rule of the fourth-century monk and leading churchman St. Basil, and the Institutes and Conferences of the fifth-century monk John Cassian, who brought the teachings of the Desert Fathers from Egypt and Judea to Gaul and adapted them to a Western monastic context. Although Benedict compiled his Rule for contemplatives living in community, he also encourages those inclined to live a contemplative life in solitude.

"At Camaldoli, St. Romuald combined eremitic monasticism inspired by the Desert Fathers and cenobitic monasticism as prescribed in the Rule of St. Benedict and followed in Benedictine monasteries throughout Europe.

"The ascetic practices Romuald established at Camaldoli fired the spiritual ideals in following generations of men and women in an age receptive to a life of solitude in seeking an intimate dialogue with and closeness to God. The eremitic movement that flourished in the eleventh century led to the founding of the Carthusian Order, dating from 1084 and the Cistercian Order near the close of the century, in the year 1098."

The Monastery and Hermitage of Camaldoli, with its centuries-old monastic tradition, has given Roseman the wonderful and important opportunity to create drawings of monks following either a cenobitic or an eremitic life within one monastic community. "The creation of my work at Camaldoli," Roseman writes in acknowledgement, "would not have been possible without the gracious hospitality and encouragement of the monks, to whom I am deeply grateful." From the artist's text on the monastic life:

At Camaldoli that summer Roseman and Davis made a gift to the monastery of an inscribed copy of the fine art book Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, which Davis had published on the occasion of the exhibition of the artist's drawings presented by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in 1996. In his introductory text, Roseman speaks of his dedication to drawing, as with his work on the monastic life. The Introduction reproduces Two Monks Bowing, Abbey of Solesmes, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The monks were appreciative of the gift and especially interested in the artist's text on drawing, as Camaldoli conserves several paintings by Vasari to whom Roseman pays tribute in his text: "That drawing is considered the foundation of the visual arts nurtured my early convictions as to the importance of drawing and the time given to my work as a draughtsman. For Vasari drawing was the animating principle of the creative process. . . .''[9]

"I was looking forward to seeing again Don Antonio, the first hermit whom I had drawn in my work on the monastic life. I remember well that snowy morning in January 1979 and driving from the monastery up the winding mountain road through the dense forest veiled in white. Snow was piled on the sides of the newly ploughed road ascending higher and higher. Emerging from what seemed like a tunnel of snow-covered pine boughs into a forest clearing, I was impressed seeing the centuries-old Sacro Eremo, which I had only known through my reading and studies. . . .''

"I accompanied Padre Placido through the gates beyond the church and into the compound of some twenty individual hermitages, arranged in five rows. The Prior explained that each hermitage, a modest, stone dwelling, has a small garden area bounded by walls. White smoke drifted out from hermitage chimneys as the wintry aroma of burning logs permeated the cold mountain air.

"Don Antonio greeted me warmly when we were introduced by the Prior. After the three of us conversed for a few minutes, Padre Placido left me in the company of the hermit monk who was to become a friend.

"On that first morning with Don Antonio, I learned that he is an astronomer. Antonio showed me the workings of the telescope that stood in the snow-covered garden of his hermitage. I expressed great interest as the telescope brought back memories of my youth when my dear father brought me on several occasions to the Hayden Planetarium in New York City and gave me a birthday gift of a small planetarium by which I could learn about the stars and project images of the constellations on the ceiling of my room.

"The monastic precept ora et labora, prayer and work, as specified in the Rule of St. Benedict, counsels the monk to balance hours of prayer with times for work. Don Antonio charted weather conditions and made meteorological reports for the Italian Weather Bureau.''

6. Monastery of Camaldoli,

Sixteenth-Century Cloister

Sixteenth-Century Cloister

The Prior General Don Emanuele said to Roseman and Davis that the artist's work is very meaningful and an important contribution to monasticism. Don Emanuele thoughtfully mentioned that the beautiful portrait Roseman had drawn of Don Benedetto in 1979 and presented as a gift to the monastery was very much appreciated and that Don Benedetto always spoke with admiration for the artist and his work on the monastic life.

"Dante refers to the celebrated Hermitage in the Apennines in his epic poem The Divine Comedy. 'Oh,' replied he, 'at foot of the Casentino crosses a stream named Archiano, which rises in the Apennine above the Hermitage.' The great Florentine poet eulogizes the saintly founder and his brethren: '. . . here is Romualdus, here are my brethren, who within the cloisters their footsteps stayed and kept a steadfast heart.' ''[7]

Dr. Henri Pauwels, Chief Curator of the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, and Mrs. Phil Mertens, Chief Curator of the Department of Modern Art, acquired in 1986 the drawing of Brother Paolo and a portrait of the elderly Benedictine monk Father Xavier from Pannonhalma Monastery, Hungary. In a cordial letter to Ronald Davis, who introduced his colleague's work to the museum, the distinguished Curators acknowledge receipt of:

We are very pleased that they will have the opportunity

to find their place in the collection of drawings of the Modern Art Department.''

to find their place in the collection of drawings of the Modern Art Department.''

"the two beautiful drawings by Stanley Roseman Father Xavier and The Young Hermit Paolo in Choir. . . .

Roseman relates in his remembrances of Camaldoli the cordial welcome he received from Don Placido, the Prior of the Sacro Eremo. The Prior brought Roseman into the enclosure where, as the artist describes, "a paved stone courtyard led to the church, built on the site of the original eleventh-century chapel. The church underwent successive rebuilding and renovations over the centuries. The present gray and white facade dating from 1713-1714 is flanked by twin bell towers rising above the Hermitage.

In the weeks that followed, Roseman had the memorable experience of sharing in the life at the Sacro Eremo. With a growing friendship with Don Antonio, Roseman visited him at his hermitage to draw the monk at work, study, and in meditation. The Prior Don Placido invited Roseman to take his meals with the hermits who gather for the daily common meal in the Hermitage refectory and to draw them in choir at the mid-day offices and at Vespers in the late afternoons while the hermit monks prayed and chanted the Psalms.

The following year, Roseman sent Don Antonio a copy of the photograph Davis took of them at the hermitage that snowy winter of 1979, (fig. 7). Don Antonio thoughtfully responded with a postcard reproducing an eighteenth-century engraving of St. Romuald, with the caption "Fondatore di Camaldoli, Eremo e Monastero."

An Exchange of Gifts

"Dear Stanley,

Thank you for your letter and the photo.

Today is the first snowfall.

Best wishes for your work and also to your friend Ronald.

We all remember you with much affection. May the Lord bless you.

Antonio - S. EREMO - November 3''

Thank you for your letter and the photo.

Today is the first snowfall.

Best wishes for your work and also to your friend Ronald.

We all remember you with much affection. May the Lord bless you.

Antonio - S. EREMO - November 3''

In the intimacy of Don Costanzo's hermitage at the Sacro Eremo of Camaldoli in 1998, Roseman drew the hermit illuminated by a summer sunlight entering from a window of his cell, (fig. 9).

9. Don Costanzo,

Portrait of a Hermit, 1998

Sacro Eremo di Camaldoli

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Collection Ronald Davis

Portrait of a Hermit, 1998

Sacro Eremo di Camaldoli

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Collection Ronald Davis

Roseman and Davis were appreciative to receive a gift from their longtime friend Don Thomas Matus, theologian, musicologist, author, and the subject of a suite of excellent portrait drawings by Roseman that summer at Camaldoli. Don Thomas's gift The Mystery of Romuald and the Five Brothers is an enlightening book that relates a history of the founder of Camaldoli along with the author's own personal reflections and his translations of the hagiographic texts by Bruno of Querfurt (d.1009), a disciple of St. Romuald; and Peter Damian, an eleventh-century Camaldolese monk. Don Thomas Matus thoughtfully inscribes his book: "To my dear friends Stanley and Ronald, With gratitude for your presence, with prayer for your work, with blessings on your life.''

© Photo by Ronald Davis

Don Costanzo is a further excellent example of Roseman's painterly use of the chalk medium for portraiture. Fine modeling describes the hermit monk's face in profile; blended chalks give warmth to shading complemented by silvery tones of Don Costanzo's long, full beard. With a harmonious synthesis of line and tone, Roseman created a deeply moving portrait of the elderly hermit in prayer.

© Photo by Ronald Davis

Photo courtesy of the Monastery

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

Returning to the Sacro Eremo in 1998, Roseman created a suite of impressive drawings of Don Antonio. The intervening nineteen years had enhanced the hermit monk's ascetic appearance.

"The Prior led me up a snowy path to the hermitage of Don Antonio. In anticipation of meeting a hermit, I was expecting to meet an elderly, white-bearded monk, but Don Antonio was in his forties and clean-shaven, a nice-looking man with short, black hair. The lines that seemed etched on his cheeks and brow bespoke, however, of his asceticism and eremitic life.

"At Camaldoli, situated only some 50 kilometers east of Florence, I paid homage to a Florentine Renaissance aesthetic in using red chalk for a series of drawings of Camaldolese monks. Leonardo da Vinci is credited with having introduced red chalk, or sanguine, for drawing during his early Florentine period from around 1475-1480.[8] Red chalk brings a warm chromatic element to a drawing and complements black and white chalks, which predate sanguine as a graphic medium. Raphael employed red chalk for drawing in the years he worked in Florence, from 1504-1508, as did Michelangelo in his return to the city after 1516. Red chalk was also taken up by other dedicated Florentine draughtsmen including Fra Bartolommeo, del Sarto, Pontormo, Bronzino, and Vasari, as well as numerous other artists through the Cinquecento.''

5. The Young Hermit Paolo

in Choir, 1979

Sacro Eremo di Camaldoli, Italy

Red chalk on paper, 48 x 33 cm

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts

de Belgique - Art Moderne,

Brussels

in Choir, 1979

Sacro Eremo di Camaldoli, Italy

Red chalk on paper, 48 x 33 cm

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts

de Belgique - Art Moderne,

Brussels

In the drawing The Young Hermit Paolo in Choir, Roseman's use of red chalk on ochre paper imbues the composition with a warm tonality. The striking mise-en-page with its strong diagonal divides the page into two parts, the seated figure enveloped in his robes and the extent of pictorial space. The artist's wide range in the application of the single red chalk renders the figure with fine lines, sweeping curvilinear strokes, and parallel- and cross-hatching complemented by translucent tonal passages and opaque shading. Roseman has effectively used reserved areas of the ochre paper to indicate light falling on the front of the habit and illuminating the face and beard of the young hermit absorbed in meditation and prayer.

© Stanley Roseman

In the present work Don Antonio, Portrait of a Hermit, (fig. 8), the artist drew with vigorous strokes of black chalk complemented by chiaroscuro modeling of the chalks, warm shading, cool skin tones from reserved areas of gray paper, and luminous white highlights on the face of the monk, his head inclined and eyes lowered as he prays.

This masterly rendered portrait of the hermit Don Antonio is exemplary of Roseman's work "profoundly expressive of the individual and the interior life,'' (Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

1. The Four Monastic Orders

of the Western Church

of the Western Church

2. Benedictines

3. Cistercians and Trappists

4. Trappists Continued

5. Carthusians

On the bottom of this page

are links to pages 2 - 5.

are links to pages 2 - 5.

Roseman created his monumental oeuvre on the monastic life in monasteries of the Benedictine, Cistercian, Trappist, and Carthusian Orders, the four monastic orders of the Western Church.

Sharing in the day-to-day life in the cloister, Roseman brought to realization a critically acclaimed oeuvre on the monastic life - a life centered on contemplation and prayer in observing the Biblical calls to prayer "At midnight I rise to praise you, O Lord'' (Ps. 119:62) and "Seven times a day I praise you'' (Ps. 119:164), stated by the Prophet in the Book of Psalms.

1. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris (text in French and English), Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996, p. 10.

2. Dante, La Divina Commedia, Il Purgatorio, Canto V, 94-95, translated by Charles Eliot Norton.

3. Lino Vigilucci, Camaldoli:A Journey into its History and Spirituality, (California: Source Books and Hermitage Books, 1995), p. 47.

4. Ibid, p. 50.

5. Christopher Hibbert, The Rise and Fall of the House of Medici, (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1979), pp. 37, 122.

6. Giorgio Vasari , Vasari on Technique, (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1960), p. 205.

7. Dante, La Divina Commedia, Il Purgatorio, see footnote 2 above; Il Paradiso, Canto XXII, 49-51, translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

8. Joseph Meder, The Mastery of Drawing, translated by Winslow Ames, (New York: Arabis Books, 1978), p. 92.

9. Stanley Roseman, Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, (Paris: Ronald Davis, 1996), p. 9.

2. Dante, La Divina Commedia, Il Purgatorio, Canto V, 94-95, translated by Charles Eliot Norton.

3. Lino Vigilucci, Camaldoli:A Journey into its History and Spirituality, (California: Source Books and Hermitage Books, 1995), p. 47.

4. Ibid, p. 50.

5. Christopher Hibbert, The Rise and Fall of the House of Medici, (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1979), pp. 37, 122.

6. Giorgio Vasari , Vasari on Technique, (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1960), p. 205.

7. Dante, La Divina Commedia, Il Purgatorio, see footnote 2 above; Il Paradiso, Canto XXII, 49-51, translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

8. Joseph Meder, The Mastery of Drawing, translated by Winslow Ames, (New York: Arabis Books, 1978), p. 92.

9. Stanley Roseman, Stanley Roseman and the Dance - Drawings from the Paris Opéra, (Paris: Ronald Davis, 1996), p. 9.