|

Ora et Labora

Prayer and Work |

|||||

Ora et Labora - Prayer and Work

Stanley Roseman drawing a Trappist monk on the farm, 1981.

Stanley Roseman

The MONASTIC LIFE

The MONASTIC LIFE

The Psalms

In his text Roseman writes of the ancient Judeo-Christian tradition of psalmody in monastic life:

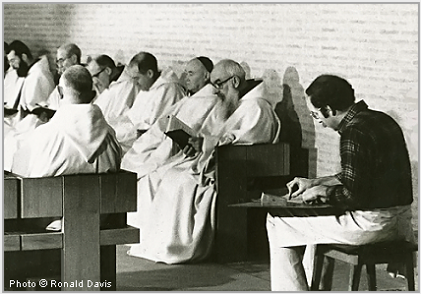

2. Stanley Roseman drawing Trappist monks in choir, 1981.

At the Benedictine Abbey of Solesmes in western France

The Times, London, published in 1980 a superlative, full-length page review on Roseman's work and featured the drawing presented above from the Abbey of Solesmes.

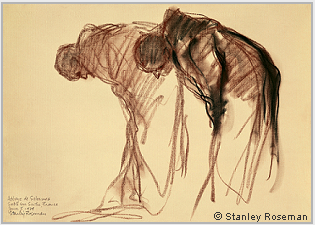

4. Two Monks Bowing, 1979

Abbaye de Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Abbaye de Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

In a gracious letter of 9 May 1995 from President Jacques Chirac to Stanley Roseman, the newly elected President of France praises the drawing:

Gregorian chant developed mainly within the context of monastic life, with the golden age of composition of the chant dating from the fifth to the eighth centuries.[6]

''No one, I believe, in 1,500 years of Christian monachism has catalogued, defined

and described so clearly or so beautifully the business of the monastic life.

No writer, no sculptor, no painter, no architect has refined a distillation so pure,

so accurate, so breathtakingly clear as Roseman has done.''

and described so clearly or so beautifully the business of the monastic life.

No writer, no sculptor, no painter, no architect has refined a distillation so pure,

so accurate, so breathtakingly clear as Roseman has done.''

- The Times, London

Prayer and Work

At the Benedictine Abbey of Engelberg in the Swiss Alps

"St. Benedict refers often to the Psalms in his Rule. Chapter 16 quotes the Prophet's call to prayer and affirms that 'this sacred number of seven' will be fulfilled by observing the seven daily offices as well as Vigils in the night. Benedict devotes chapters to how many and which Psalms are to be sung at the Night Office in winter and in summer and at Lauds on Sundays and on weekdays. Chapter 18 enumerates the order and the specific Psalms for the other daytime offices. And Benedict allocates time in the monks' daily schedule for studying the Psalms. . . .

"Chapter 19, on the discipline of singing the Psalms, states: 'We should therefore always be mindful of the Prophet's words, 'Serve the Lord with fear' and 'Sing praises wisely.' In choir the Psalms are sung in the ancient tradition from the Temple and Synagogue of antiphonal chanting, by alternate choruses or singers. Benedict instructs that as the Psalms are sung in the presence of God, they are to be sung in such a way that 'there is complete harmony between the thoughts in our minds and the meaning of the words we sing.' ''[4]

"The canonical hours, called the Divine Office, are founded on singing the Psalms. 'Lord open my lips, and my mouth will proclaim your praise,' from Psalm 51, begins Vigils, the first and traditionally the longest Office, sung to keep watch in the night.[2] At dawn, the Psalms for Lauds offer renewal and hope; at day's end, the Psalms for Compline bless the Lord and ask God for protection in the dark.

The Benedictine Abbey of Engelberg was founded in 1120 in a remote Alpine valley in central Switzerland. From the twelfth century the Abbey was an important center for book production, literary work, and manuscript illumination. The library houses an outstanding collection of manuscripts and incunabula.

Abbot Berchtold Müller was always warmly welcoming to Roseman and Davis, and the esteemed Abbot greatly encouraged the artist in his work on the monastic life.

7. Brother Kuno at Vespers

1987, Engelberg Abbey,

Switzerland

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

1987, Engelberg Abbey,

Switzerland

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

The Subprior Father Hesso, an amiable man, thoughtfully introduced Roseman to members of the community. The Subprior asked the artist if he would like to draw Brother Peter, the pastry chef, which elicited from the artist a willing smile. Roseman recounts: "Father Hesso mentioned that Brother Peter, who had worked at various jobs in his monastic vocation, had been apprenticed to a well-known Konditor (pastry chef) in Lucerne before taking on the job of pastry chef at Engelberg.

"Brother Peter prepared desserts for some three hundred students and faculty of the monastery school, in addition to lay personnel and guests, as well as for the monks themselves. Brother Peter was wonderful to draw at his work: rolling sheets of dough, mixing and blending cooking ingredients, and frosting cakes.

"Drawing in the kitchen over several mornings came with pleasant advantages, for the thoughtful pastry chef would offer me a generous portion of cake and a cup of coffee for a coffee break from my own work. And of course, I knew ahead of time what delicious desserts would be served for lunch and dinner. . . .''

"With my drawing paper and box of chalks, I walked up the mountain to Brother Konrad's cabin. At the top of some steps and beyond a gate, the beekeeper, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, was working in his garden. Beckoning me to enter, he called "bitte, bitte'' ("please, please'') in his lilting St. Gall accent, while his canine companion barked a friendly greeting.

"I began drawing the monk at work in his garden, but soon the overcast sky brought rain. Brother Konrad thoughtfully invited me into his cabin and kindly sat for me so that I could draw his portrait. The gray, afternoon light enhanced the cool highlights and warm shading on the face of the gentle monk who sat silently before me. I drew into the late afternoon until the bells for Vespers summoned us to return to the Abbey.''

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Roseman notes: "St. Benedict, following the teachings of John Cassian, instructs his monks to take care of all monastery possessions: 'that the cooking-pots must be treated with the care due to chalices.'[15] In the Rule, Chapter 31, which describes the kind of man the cellarer should be, Benedict states: 'All the utensils of the monastery and in fact everything that belongs to the monastery should be cared for as though they were the sacred vessels of the altar.' ''[16]

The eminent American collector John Davis Hatch, Co-founder and first Director of Master Drawings Association, acquired Frère Christian in the Kitchen with two portraits Padre Hipólito, Abbey of San Pedro de Cardeña, Spain, 1979, and Frère Samuel, Abbey of La Trappe, France, 1979. In an enthusiastic letter to Ronald Davis, Mr. Hatch writes in acquiring the drawings:

11. Frère Christian

in the Kitchen, 1979

Abbaye de Fleury, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

John Davis Hatch Collection

in the Kitchen, 1979

Abbaye de Fleury, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

John Davis Hatch Collection

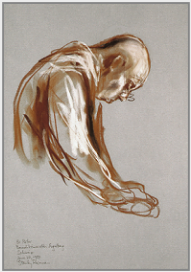

8. Brother Peter, the Pastry Chef

1987, Engelberg Abbey,

Switzerland

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

1987, Engelberg Abbey,

Switzerland

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

9. Brother Konrad,

the Beekeeper, 1987

Engelberg Abbey,

Switzerland

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Switzerland

the Beekeeper, 1987

Engelberg Abbey,

Switzerland

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Switzerland

"I very much appreciate Stanley's allowing me to have them -

as they are great additions to my drawing collection.''

as they are great additions to my drawing collection.''

- John Davis Hatch

Co-founder of Master Drawings Association

Co-founder of Master Drawings Association

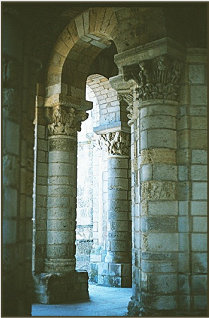

3. Benedictine Abbey of Solesmes

along the River Sarthe, within the boundaries of the historic provinces

of Maine and Anjou.

along the River Sarthe, within the boundaries of the historic provinces

of Maine and Anjou.

The revered Abbot of Solesmes warmly received Roseman and his colleague Ronald Davis on their first sojourn at the monastery in June 1979 and heartily welcomed them back on return visits to Solesmes.

The Abbot of Solesmes Dom Jean Prou greatly encouraged Roseman in his work on the monastic life. A preeminent churchman of his time, Dom Jean Prou was a Councillor Father at the Second Vatican Council. Pope John XXIII, who made several retreats at Solesmes during the time he was papal nuncio in Paris, nominated Dom Prou to the Commission for the Liturgy.

" 'Two Monks Bowing,' magnificent example of a work very successfully realized that you have consecrated to the contemplative life. I greatly appreciate the classical tradition of your draughtsmanship, the magnificently suggested volumes, the precision of the forms and proportions.

With my congratulations.''

With my congratulations.''

- Jacques Chirac

President of France

President of France

The maxim "prayer and work," ora et labora, emphasizes the importance placed on work as an indispensable part of a life centered on prayer. The following are further extracts from Roseman's text on monastic life:

"St. Benedict in his Rule acknowledges the teachings of his predecessors St. Basil and John Cassian, in the fourth and fifth centuries respectively, and instructs that the Divine Office be complemented by manual work and sacred reading (lectio divina). Benedict follows the earlier, sixth-century Rule of the Master that prescribes as essential to the contemplative life both manual work and sacred reading in the intervals between the hours of the Divine Office.[8]

"The Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 48 'The Daily Manual Labor' begins: 'Idleness is the enemy of the soul. For this reason the brethren should be occupied at certain times in manual labor, and at other times in sacred reading.'[9] However, the interpretation of what constitutes work in monasteries and the definition of work in a broader sense other than manual labor, such as literary work, is one of the reasons for the diversity in the development of Western monasticism. . . .

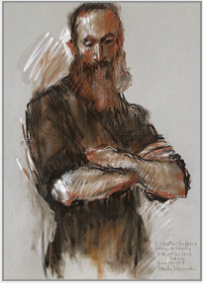

12. Frère Christian, 1979

Abbaye de Fleury, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

New Orleans Museum of Art

Abbaye de Fleury, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

New Orleans Museum of Art

At the Benedictine Abbey of Fleury along the Loire

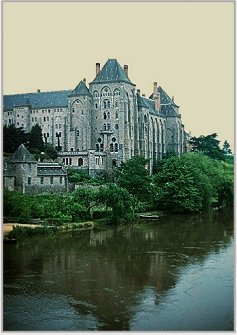

"In the year 651, under the reign of Clovis II, a monastery was founded along the banks of the River Loire, some thirty kilometers east of Orleans, at an ancient site called 'Floriacum.'

"The great abbey church, with the reliquary of St. Benedict in the crypt, is an impressive example of Romanesque architecture. Built between the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the abbey church is notable for its tower porch and belfry 'vaulted in nine compartments over four interior supports on each level, with elaborate sculpted capitals.' "[14]

10. The Romanesque tower porch

of the Abbey of Fleury, France.

of the Abbey of Fleury, France.

At the Abbey of Fleury in the summer of 1979, Roseman drew the cook Frère Christian at work in the monastery kitchen, (fig. 11).

In a letter of appreciation to the generous donor, the Museum's Chief Curator Valerie Loupe Olsen writes in receipt of the drawings Frère Christian, Abbey of Fleury, 1979, and Sister Elsa in Choir, Östra Sönnarslövs Kloster, Sweden, 1982:

"Scholarship and literary work became hallmarks of Benedictine monasticism, with notable contributions in different fields of study. . . . Composers, musicians, and musicologists owe a debt of gratitude to the eleventh-century Benedictine monk, author, and music theorist Guido of Arezzo, whose invention of staff notation using syllables is the basis of the standard musical scale of today.''[10]

"I have just received them today and they are truly beautiful drawings

and a welcome addition to our collection.''

and a welcome addition to our collection.''

- Valerie Loupe Olsen, Chief Curator

New Orleans Museum of Art

New Orleans Museum of Art

Gregorian chant has its origins in the singing of the Psalms in ancient Jewish liturgical worship in the Temple and the Synagogue.[7] Psalmody, the singing or chanting of the Psalms, is the foundation of the Divine Office, the daily round of communal prayer that is central to the monastic life.

"By the ninth century, the Abbey of Fleury had become an important place of pilgrimage as the monastery houses the relics of St. Benedict. His last monastery at Monte Cassino was destroyed by the Lombards in c.580, and the grave of the saint lay for a century among the ruins. In the late seventh century the Abbot of Fleury initiated a search party that went to Monte Cassino to salvage the remains of St. Benedict and his sister St. Scholastica. The remains of St. Scholastica were brought to Le Mans, and those of St. Benedict, to Fleury, also known today as the Abbey of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire.[13]

The monastic precept "prayer and work,'' in Latin "ora et labora,'' goes back to early Christian monasticism in the deserts of fourth-century Egypt and Judaea, where work - that is manual labor - was necessary to support a life centered on contemplation and prayer. Work as a complement to prayer was later reaffirmed in the Rule of St. Benedict, a sixth-century document by the saintly Italian abbot Benedict of Nursia (c.480-547), revered as the Father of Western monasticism. The Rule of St. Benedict, which consists of a Prologue and seventy-three short chapters that give spiritual counsel and regulations for communal life in a monastery, is the basis of monastic observance in the Western Church.

Stanley Roseman's interest in the monastic life, which as he writes "is interwoven with the history and culture of Europe;'' his studies on monasticism; and the encouragement of those whom he came to know in the monastic world led the artist to write a text on monastic life and his work in monasteries to accompany his paintings and drawings. The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green, having kindly read a draft of Roseman's manuscript, writes in a cordial letter to the artist:

"I would like to thank you very much for your paper on monasteries and monasticism,

which I have read with great pleasure and interest. You portray the background and the aims of life

in monasteries so well, showing such deep understanding of the monastic life.''

which I have read with great pleasure and interest. You portray the background and the aims of life

in monasteries so well, showing such deep understanding of the monastic life.''

- Dom Bernard Green, OSB

St. Benet's Hall, Oxford

St. Benet's Hall, Oxford

Roseman's work on the monastic life brought him to the Benedictine Abbey of Solesmes, renowned for the study and restoration of Gregorian chant, a reverential musical expression associated with singing the Psalms.

"In the mid-seventeenth century, Solesmes joined the newly founded Congregation of St. Maur, headquartered at the ancient Abbey of St. Germain des Pré, in Paris, and actively engaged in scholarship and literary work. Heir to the Maurist tradition, Solesmes, which had been dissolved along with other religious orders during the French Revolution, was restored in 1833. Four years later, Solesmes was elevated to the rank of an abbey and the head of a new Benedictine Congregation in France. . . .[5]

"Today, the Congregation of Solesmes includes monasteries in Europe, United States, Canada, Argentina, Senegal, and Martinique."

"The Book of Psalms, or Psalter, consists of 150 Psalms. Following the number and title of many of the Psalms are inscriptions that are taken to refer to the author or to a relationship with the person so named, including Moses (Ps 90), Solomon (Ps 72), and David, who is traditionally credited with composing a large part of the Psalter. . . .

"The Psalms were organized into five books, as with the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Old Testament.[3] Some of the Psalms are hymns of praise and thanksgiving; others express sorrow and suffering. Some are Psalms of pilgrimage; others are Psalms of repentance. Some are meditations or long prophetic poems; other Psalms seek God's help and celebrate His holy name.

The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., conserves Roseman's spiritual work of art drawn at the Divine Office and depicting two monks bowing in prayer, (fig. 4).

The Abbey of Solesmes gave Roseman the important opportunity to create work in the leading monastery engaged in the modern restoration of Gregorian chant.

''The Prophet states in the Book of Psalms, 'At midnight I rise to praise you,' and 'Seven times a day I praise you.' This Biblical call to prayer from Psalm 119, 'In praise of the divine Law,' gives monastic life its definitive form and structure.[1] The monastery bell tolls the Night Office, or Vigils, and the daytime Offices of Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, and None, Vespers in the late afternoon, and Compline at the end of the day.

"From the sixth through the twelfth centuries, when many monastery scriptoria were flourishing centers of writing, copying, and illuminating manuscripts, monasteries produced most of the books in the West.

Among Dom Mallet's literary works is a translation of the Life of Saint Benedict, written in the late sixth century by Pope Saint Gregory the Great, himself a monk before elected to the papacy in 590. Dom Mallet co-authored and inventoried the 12th- to 13th-century Antiphonaire monastique: Benevento, Biblioteca capitolare, 21.

Roseman's work brought him in the summer of 1979 to the French Benedictine Abbey of Fleury, which has a long and distinguished history as the artist relates:

© Photo by Ronald Davis

© Photo by Ronald Davis

© Photo by Ronald Davis

The Abbey of Solesmes rises impressively above the Sarthe River, within the boundaries of the historic provinces of Maine and Anjou. In recounting his work at Solesmes, Roseman relates some facts about the Monastery's history which began with the founding of a priory in the year 1010.

Recounting his sojourns at Engelberg, Roseman writes: "I was given the wonderful opportunity to view and study a number of manuscripts which the kind archivist Father Urban brought to my attention for their exceptionally fine illuminations. . . ."

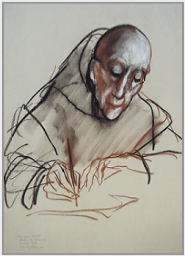

5. Dom Jean Mallet

at his Desk in the Atelier de

Paléographie Musicale

1998, Abbey of Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, France

at his Desk in the Atelier de

Paléographie Musicale

1998, Abbey of Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, France

Dom Jean Mallet at His Desk in the Atelier de Paléographie Musicale, 1998, exemplifies Roseman's skillful handling of the chalk medium in combining linear description and chiaroscuro modeling. Fluent lines establish the pyramidal composition in the drawing of the Benedictine monk at his desk and give a sense of movement of his right hand employing a writing instrument, his left hand touching an edge of the paper. Transparent passages of the chalks add tone to the monk's scapular and hood but give precedence to the identity of the line describing shape and volume. The artist has beautifully modeled with strong highlights and warm shading the face of the ascetic monk absorbed in his work.

Speaking about the present work, Roseman writes: "I drew predominantly in bistre and white chalks, with touches of black on the gray paper to render the pastry chef bent over his marble countertop, his small round glasses low on his nose, as he intently kneaded and rolled by hand pastry dough."

1. The Psalter is comprised of one hundred and fifty Psalms. Psalms 10 to 148 in the Hebrew Bible are one number ahead of the Greek

Septuagint and Latin Vulgate Bibles. The Greek and the Vulgate combine Psalms 9 and 10 as well as Psalms 114 and 115 while

separating into two parts each Psalm 116 and Psalm 148. The Rule of St. Benedict uses the numbering of the Psalms in the Vulgate Bible.

2. Psalm 51 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 50 in the Vulgate.

3. Klaus Seybold, Introducing the Psalms, (T&T Clark, Scotland, 1990), pp. 16-23.

4. The Rule of St. Benedict English translations by Abbot David Parry, O.S.B., Households of God, (Darton, Longman &Todd, London,

1980), and Abbot Patrick Barry, O.S.B., St. Benedict's Rule, (Ampleforth Abbey Press, 1997).

5. Louis Soltner, Solesmes and Dom Guéranger 1805-1875, (Orleans: Massachusetts, Paraclete Press, 1995), pp. 48 and 132.

6. "Early Medieval Music,'' New Oxford History of Music, ed. Dom Anselm Hughes, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954), Vol. II, p. 101.

7. Ibid., pp. 1, 93, 94.

8. The Rule of the Master, translated by Luke Eberle, O.S.B., (Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1977), pp. 208, 209.

9. Parry, Households of God, p. 77.

10. New Oxford History of Music, pp. 291, 292.

11. Pierre Rosenberg and François Bergot, French Master Drawings from the Rouen Museum from Caron to Delacroix,

(Washington, D.C.: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1981), p. vii.

12. The Lives of the Desert Fathers, translated by Norman Russell, (London & Oxford: Mowbray, 1981), pp. 13, 15.

13. J.-M. Berland, Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, (Paris: Nouvelle Editions Latines), pp. 6-7.

14. Kenneth John Conant, Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture 800-1200, (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1973), p. 155.

15. Owen Chadwick, John Cassian, Second Edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), p. 67.

16. Barry, St. Benedict's Rule, p. 38.

Septuagint and Latin Vulgate Bibles. The Greek and the Vulgate combine Psalms 9 and 10 as well as Psalms 114 and 115 while

separating into two parts each Psalm 116 and Psalm 148. The Rule of St. Benedict uses the numbering of the Psalms in the Vulgate Bible.

2. Psalm 51 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 50 in the Vulgate.

3. Klaus Seybold, Introducing the Psalms, (T&T Clark, Scotland, 1990), pp. 16-23.

4. The Rule of St. Benedict English translations by Abbot David Parry, O.S.B., Households of God, (Darton, Longman &Todd, London,

1980), and Abbot Patrick Barry, O.S.B., St. Benedict's Rule, (Ampleforth Abbey Press, 1997).

5. Louis Soltner, Solesmes and Dom Guéranger 1805-1875, (Orleans: Massachusetts, Paraclete Press, 1995), pp. 48 and 132.

6. "Early Medieval Music,'' New Oxford History of Music, ed. Dom Anselm Hughes, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954), Vol. II, p. 101.

7. Ibid., pp. 1, 93, 94.

8. The Rule of the Master, translated by Luke Eberle, O.S.B., (Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1977), pp. 208, 209.

9. Parry, Households of God, p. 77.

10. New Oxford History of Music, pp. 291, 292.

11. Pierre Rosenberg and François Bergot, French Master Drawings from the Rouen Museum from Caron to Delacroix,

(Washington, D.C.: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1981), p. vii.

12. The Lives of the Desert Fathers, translated by Norman Russell, (London & Oxford: Mowbray, 1981), pp. 13, 15.

13. J.-M. Berland, Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, (Paris: Nouvelle Editions Latines), pp. 6-7.

14. Kenneth John Conant, Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture 800-1200, (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1973), p. 155.

15. Owen Chadwick, John Cassian, Second Edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), p. 67.

16. Barry, St. Benedict's Rule, p. 38.

Portraiture holds an important place in Roseman's oeuvre on the monastic life. Aftonbladet, Stockholm, the leading Swedish daily, in a Sunday magazine cover story on the artist in 1979, commends Roseman for creating portraits "artistically on a high level as well as accurately expressive of the human dimension.''

Portraiture

© Stanley Roseman

A traditional work in Benedictine monasteries is the administration of a monastery school, with a number of the monks on the faculty, as with Brother Kuno, a teacher of mathematics at Engelberg's highly respected private school. Brother Kuno at Vespers depicts the tall, dark-haired monk standing in choir. Roseman draws the monk's habit with broad, sweeping strokes of black and bistre chalks combined with the blending of the chalks. Detailed modeling, heightened with white, describes the young man's face seen in profile, his head bowed in reverence as he prays.

In the drawing Brother Peter, the Pastry Chef, Roseman combines vigorous strokes, fine lines, and painterly modeling of the chalks to depict the pastry chef seen in profile. The powdery white on the monk's sleeve and collar are complemented by luminous highlights on his face and cranium. The drawing eloquently expresses the monk's outward appearance in his mature years, the action of the pastry chef rolling pastry dough, and the interiority of the man who has dedicated a life to prayer and work. As with the drawing Brother Kuno at Vespers above, Brother Peter, the Pastry Chef is a further example of Roseman's consummate draughtsmanship.

In the excellent drawing Frère Christian in the Kitchen, the viewer perceives the care that the monk is taking to clean a cooking pot. Here Roseman draws with broad, vigorous strokes of chalk complemented with a lively interplay of line and tone, as in the depiction of Frère Christian's black tunic and dark hair and beard. Painterly modeling of the chalks describes the monk's right forearm and the large, metallic cooking pot, with its shimmering reflections, in the foreground of the composition.

The New Orleans Museum of Art acquired the portrait drawing Frère Christian, (fig. 12). Roseman relates: "When Frère Christian finished his chores in the kitchen, I asked him if he could please stay a while longer for me to do a portrait drawing of him. He kindly said he would give me whatever time I needed for my work.''

© Stanley Roseman

The impressive three-quarter length portrait of Frère Christian is rendered with chiaroscuro modeling of the chalks. Roseman depicts the bearded, Benedictine monk in a moment of repose. The sleeves of his black tunic are rolled up. Folded across his chest, the monk's muscular forearms are evident of the hours he engaged in manual labor complementing the hours he devoted to prayer.

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

''A stunning series of drawings depicting the monastic life in Europe.''

- Associated Press, Rome

6. Benedictine Abbey of Engelberg, situated in an Alpine valley at an altitude of 2000 meters, in Canton Unterwalden, Switzerland.

At Engelberg Abbey, Roseman was invited to draw Brother Konrad, whose impressive portrait Brother Konrad, the Beekeeper, 1987, (Private collection, Canton Lucerne), is presented below, (fig. 9). Roseman writes: "Beekeeping was an occupation of monks from the time of the Desert Fathers in fourth-century Egypt and Judea, for honey is a nourishing food as well as a medicament.[12] Beekeeping is still a work in monasteries today.

"Brother Konrad, a monk of slight build and with a rosy complexion and friendly eyes, worked at his cabin on a mountainside a short distance above the monastery. He tended a garden, raised chickens for eggs, and cared for the honeybees in the apiary behind his dwelling. Brother Konrad had an Alpine herding dog, a Bernese sennenhund, who pulled a cart with supplies up the mountain and, with cartons of eggs and jars of honey, down to the monastery kitchen.

- The Boston Globe

"Roseman has captured the personalities of many individual monks while often managing to depict their lifestyles as well. . . . The artist's gray, brown, dark and light tones vary as subtly and surely

as the monks who live out their discipline of prayer and work and meals in common.''

as the monks who live out their discipline of prayer and work and meals in common.''

Roseman's drawings expressive of prayer and work include Brother Kuno at Vespers, 1987, (fig. 7), and Brother Peter, the Pastry Chef, 1987, (fig. 8, below). The Chief Curator of the Museums of France and Director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Rouen, François Bergot, praised the "very beautiful drawings" in making his third acquisition in 1988 of Roseman's work for the Museum, "whose collections of paintings and drawings are among the most complete and most renowned in France," (French Master Drawings from the Rouen Museum, 1981).[11]

Roseman's work in monasteries includes a number of drawings of monks and nuns engaged in scholarly pursuits. From the Abbey of Solesmes is the marvelous drawing of the distinguished musicologist Dom Jean Mallet at his desk in the Atelier de Paléographie Musicale, the extensive music library of the monastery, (fig. 5).

A Selection of Roseman's drawings of daily life in monasteries in Europe

1. Ora et Labora -

Prayer and Work

2. Daily Life in the Monastery

Prayer and Work

2. Daily Life in the Monastery

On the bottom of this page

is the link to page 2.

is the link to page 2.

The eminent Abbot of Solesmes Dom Jean Prou writes in letter of appreciation in July 1980 to Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis:

"Please know, dear friends, of my sincere remembrances in the Lord."

- Dom Jean Prou, OSB

Abbot of Solesmes

Abbot of Solesmes

"Thank you for sending me a copy of the article from 'The Times' that relates your monastic and artistic tour; I see there that Solesmes has a good place. Be assured that you also have a good place in my prayers, and I often ask God to shower you with His favors.

(See further correspondence from the Abbot of Solesmes on the website page "Correspondence from the Monasteries.")